Introduction

Recently, Badmovies contributor Thomas Hortian—whom I owe the opportunity to even be able to rant about films here in the first place—sent me a few science-fiction relics from the 1950s. Unfortunately, we arrived at this topic through the death of Bert I. Gordon, in the course of which we discussed his films. Up to that point, I hadn’t yet seen some of his early works, and as mentioned, Thomas simply sent me a few of them: among them his debut King Dinosaur (1955), as well as Beginning of the End (1957) and The Cyclops (1957).

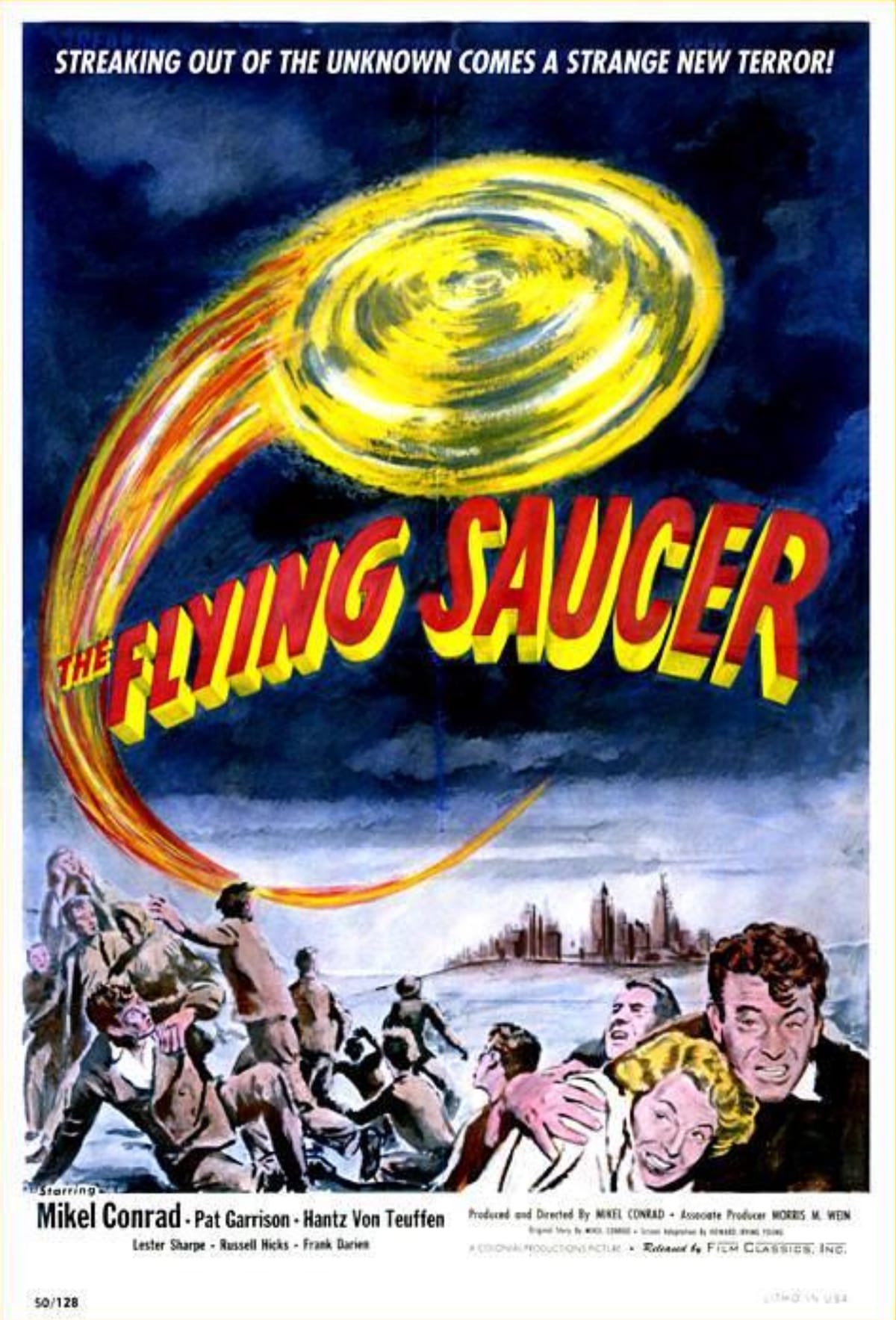

But today isn’t actually about Mr. BIG (may he rest in peace). In any case, I wanted even more of those old, dusty sci-fi flicks that have never been released in Germany (and probably never will be). One of them was The Flying Saucer from 1950, right at the very beginning of the great 1950s alien/mutant/monster wave. On top of that, it was the very first film ever to deal with the phenomenon of flying saucers (a.k.a. UFOs).

And films with UFOs—or even just a single one—tend to spark at least a basic level of interest, don’t they? Later works like The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) or Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956) were certainly quite entertaining. And the legendary hubcap UFOs from Ed Wood’s Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959) hardly need to be mentioned at this point.

Plot

“We gratefully acknowledge the cooperation of those in authority who made the release of the ‘Flying Saucer’ film possible at this time.”

The film opens with these lofty words. The camera pans across treetops before slowly lowering to the ground, where a person enters a cave. A few seconds later, a flying saucer shoots out of the cave and disappears into the night.

Newspapers flutter into the frame, announcing sightings of the unknown flying object. This is further illustrated by shots of people staring wide-eyed at the sky, clutching their heads (they seem to be suffering from severe migraines). In the final of these sequences, a woman slowly turns toward the camera, blinking violently, stares straight into the lens, and then screams at the top of her lungs. What exactly did she see on the ground? I thought UFOs were supposed to fly. Or was the cameraman just particularly ugly?

We then move to Washington—more precisely, to the small office of Hank Thorn. He has summoned Mike Trent, who sits casually at his desk, laughing his head off at the reports. Thorn, however, finds the matter far less amusing. After all, whichever nation uncovers the secret of the object first would dominate the world—and the Russians are apparently already searching for it. On top of that, the UFO could theoretically drop atomic bombs anywhere in the United States.

Trent stops laughing once he learns that he’s supposed to take on the assignment himself. The UFO was reportedly sighted in Alaska, and since Trent used to live there, he seems well suited for the job—especially given reports of communist agents already operating in the area. Mike initially refuses, at least until he’s introduced to his assigned partner: Agent Vee Langley.

Disguised as a nurse and a patient, the two set off together by ship toward the far north of the American continent.

Background and Review

I would argue that 1950s science-fiction films fall into at least three categories. First, there are those that are genuinely well made, both in terms of content and craftsmanship, and can still be watched seriously today—films like 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) or The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957).

The second category includes films that are utterly, spectacularly stupid and cheap, but precisely because of that, immensely entertaining—entries such as Robot Monster (1953) or Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959). Then there are dozens of films that fall somewhere in between these categories.

The third category consists of films that are simply unwatchable. Taste in film is debatable, but there are certain works that one cannot reasonably call entertaining—simply because they cannot be. In this category, the posters and titles often represent the very best the production has to offer. A prime example of such an obviously terrible film would be Mesa of Lost Women (1953). And unfortunately, I now have to include The Flying Saucer in this category as well.

The beginning, at least, is fairly promising. There are theatrically screaming women (one even looks straight into the camera), ominous newspaper headlines, and even effects. The film immediately establishes what it’s about and doesn’t keep the audience waiting—at least not at first. After this oddly amusing, wonderfully naive and bombastic opening, however, the dull chatter begins.

The two “heroes” seem to have been lifted straight from the handbook of boring 1950s sci-fi stereotypes. The laid-back hero Mike Trent only joins the mission because he’s paired with the confident Agent Vee, who looks exactly like every other female lead in B-movies of the era. After leaving Washington, most of the film takes place in Alaska—not a bad thing in itself, especially since director Mikel Conrad (who also plays Trent) actually traveled there! Less scrupulous filmmakers would have shot everything in dull quarries or caves and padded it out with stock footage.

Unfortunately, even the relatively attractive scenery doesn’t help if nothing happens. Mike and Vee bicker a bit, take boat rides, walk through the wilderness, sit around in a house—and (spoiler alert!) grow closer to each other. Who could have guessed?

The problem is simple: the film never gets going. There’s endless talk about the flying saucer, but we hardly ever see it—and certainly never in action. And as if that weren’t bad enough, after about 40 minutes the whole mess is revealed to be something far more mundane and man-made. No aliens, no invaders from outer space, nothing that might have been interesting. The “UFO” turns out to be an invention by some scientist who isn’t even allowed to be a proper mad scientist, while his assistant wants to sell the thing to the communists.

Once the cat is out of the bag, any remaining hope that something worthwhile might still happen completely evaporates. From that point on, the already thin plot is padded out with endless flying scenes featuring Mike staring blankly out of windows, accompanied by an incredibly annoying and overly loud soundtrack.

In the end, there are simply no real spectacle values. The “highlights” consist of a few poorly filmed fistfights, stock footage of bears and ice floes, and a few seconds of flying saucer footage. To be fair, the saucer itself doesn’t even look that bad—but that hardly matters when everything surrounding it is staged in such a dull and lifeless manner. With more proper effects and a screenplay that had even a single creative idea, this could have been something much better.

It’s worth noting that director Mikel Conrad claimed these scenes were based on realistic photographic material provided by the government and that he himself filmed on location in Alaska—a rather unusual marketing strategy.

This brings us to the cast. Mikel Conrad as Mike Trent (who, incidentally, smokes like a factory chimney in nearly every scene) delivers a serviceable performance under the circumstances and at least does something “useful,” though he never comes across as particularly likable. As an actor, he mostly appeared in uncredited bit parts elsewhere, including the American versions of Godzilla films. He clearly had no talent as a director, which explains why this was both his first and last directing effort.

He also co-wrote the screenplay, though that’s hardly an achievement once you subtract the boat rides and flight scenes. He shared writing duties with Howard Irving Young, who had been writing screenplays and stage plays since 1915, though none of them are particularly well known or related to science fiction—assuming one even wants to classify The Flying Saucer as pure science fiction. It’s really more of a Cold War thriller.

Trent’s female companion is played by Pat Garrison, who appears in her only leading role here. She otherwise never made much of an impression, apart from an uncredited role in Head Over Heels in America (1985). She has very little to do—actually, nothing at all—since Vee barely does anything either. Her behavior is nonetheless maximally stupid: she strolls through the woods, sees a bear (which makes no attempt to attack her), and immediately lets out a good long scream.

Hantz von Teuffen, who plays the somewhat odd caretaker Hans, also served as producer of the film but never appeared in any other roles afterward. His later life, however, was far more interesting. Hans Johann Franz Oskar von Meiss-Teuffen (his real name) was an adventurer, traveled through Africa, and worked as an agent during World War II. Several versions of this phase of his life exist, and his Wikipedia entry makes for quite an interesting read. He also wrote several travel books. How he ended up involved in this film remains unknown. From 1946 onward, he lived in New York for a while and gave radio interviews there.

Frank Darien, the cast member with the second-highest number of credits (235 according to IMDb), plays nothing more than a hopeless drunk who gets shot by the Russians. Speaking of gunfire, it’s worth mentioning that bullets apparently have no effect on the mighty Trent. When the evil Russian unloads an entire submachine gun magazine at close range, another Russian serving as a human shield is more than sufficient protection.

The traitorous Turner is played by Denver Pyle, arguably the most recognizable actor in this entire production. With 264 credits to his name, his most famous role is likely that of the lawman in Bonnie and Clyde (1967).

Conclusion

The Flying Saucer is a completely tensionless, thoroughly unspectacular little film that has rightly faded into obscurity. The main issue isn’t necessarily the available effects or the actors, but simply the fact that far too little of interest happens. As trash entertainment, the film fails entirely—apart from the slightly amusing opening already mentioned.

And since it isn’t even a real alien film, as one might hope, even completists of 1950s science fiction can safely skip this one. The film isn’t outright infuriating, but given the era in which it was made, one can’t help but wonder why so little was done with its premise.

Several telegrams shown in the film indicate that the story is set in the summer of 1949—barely two years after the famous Roswell incident that sparked the UFO wave in the United States. Did no one on the crew think they could make something more interesting out of this premise than a mediocre story about communist agents?

In the end, the first “UFO film” is unfortunately anything but what it could—and should—have been.