Introduction

As the title clearly suggests, today’s subject is Bigfoot, the old shaggy fellow. He is probably the most famous creature in cryptozoology, mainly because—unlike the Mothman or the New Jersey Devil—he is not merely sighted sporadically, but supposedly on a more or less “continuous” basis, which allowed him to firmly establish himself in pop culture. The only remotely comparable figure from this pseudoscientific field would be the Loch Ness Monster.

The Sasquatch also comes with plenty of regional offshoots: the Skunk Ape from Florida, the Yeti in the Himalayas, the De Loys’ Ape in South America, and so on.

Unlike classic mythological figures such as Dracula, the Mummy, or the Wolf Man, however, the ape-man never managed to permanently secure a place in cinema. He only appears in a handful of films that are widely known, and for the most part exists almost exclusively in B-movies.

In the 1950s, the myth was primarily explored through the Yeti. Twice in utterly forgotten B-films like Man Beast (1956) and The Snow Creature (1954), and twice by somewhat larger studios. Hammer produced Yeti (1957), a surprisingly watchable film that approaches the myth in a more grounded way and refrains from exploiting it for cheap spectacle. Toho also made an attempt with Jujin Yuki Otoko, which was later released in the United States in a heavily altered version as Half Human – The Story of the Abominable Snowman. Unfortunately, Toho itself never gave the film a proper home video release.

There were also somewhat similar ape-related films in the 1940s, but the true catalyst that brought Bigfoot into the cinematic medium was the legendary Patterson–Gimlin film from 1967—a roughly one-minute-long piece of footage that allegedly shows Bigfoot in northern California. To this day, the film has never been conclusively debunked and is still considered the most serious candidate for a genuine cryptid recording.

Five years later, the resourceful director Charles B. Pierce produced the pseudo-documentary The Legend of Boggy Creek, which—on a modest production budget of around $160,000—reportedly grossed 25 million dollars at drive-in theaters (at least if you believe Pierce’s daughter). While Pierce didn’t directly use the Patterson–Gimlin footage as a basis, he drew from similar sightings in Fouke, Arkansas, where a humanoid ape-like creature had also allegedly been observed.

As always, success spawned countless imitators. From today’s perspective, even The Legend of Boggy Creek itself feels dull and unspectacular (at least in my opinion; 90% of the runtime consists of hillbillies and trees), and the copycats weren’t exactly better: Sasquatch: The Legend of Bigfoot (1976, in my opinion still one of the “better” entries), The Legend of Bigfoot (1975), Bigfoot: Man or Beast (1972), In the Shadow of Bigfoot (1977), In Search of Bigfoot (1976—an absolutely shameless film whose highlight is a single “footprint”), and Ungeheuer! (1976).

Aside from these cheap pseudo-documentaries, which are nearly indistinguishable from one another both narratively and visually, there were also a few films that attempted to sell fictional stories as truth. These relied on fiction and “normal,” conventional storytelling—complete with actual dialogue, characters, and dramaturgy (well, almost). In 1970, John Carradine appeared in Bigfoot (released in Germany as Big Foot – Das größte Monster aller Zeiten). This was followed by titles such as the objectively quite decent Creature from Black Lake (1976), the TV movie Curse of Bigfoot (which recycled footage from Teenagers Battle the Thing from 1958), Return to Boggy Creek (1977), Der Teufel tanzt weiter (1980), the Italian disco-infused trashfest Yeti – Der Schneemensch kommt (1978), and Shriek of the Mutilated (1974—though whether that even qualifies as a Bigfoot film is debatable, but spoilers prevent further discussion here).

Not to forget various kid-friendly versions such as Harry and the Hendersons (1987) or Cry Wilderness (1987). There were also plenty of films featuring ape-like monsters that were never explicitly called Bigfoot, or in which he appeared only briefly.

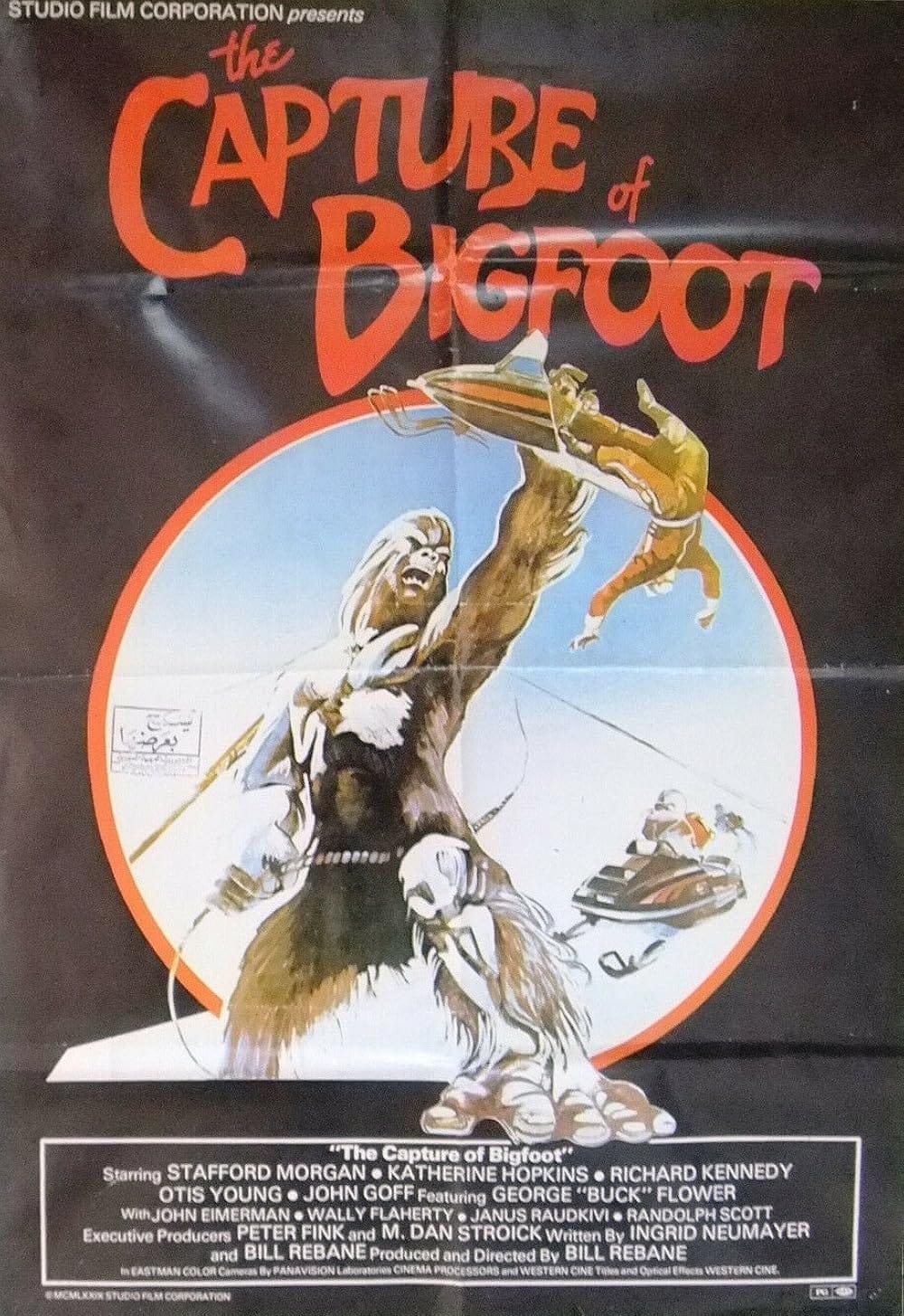

Today, however, we’re dealing with a very particular specimen: The Capture of Big Foot from 1979, released toward the end of the Bigfoot boom of the decade. In Germany, it later appeared on VHS under the titles Big Foot – Die Rache des Jägers or Die Gefangenschaft des Big Foot, though unfortunately very little information about these releases can be found online.

But enough of the preamble—let’s head into the snowy woods somewhere in America.

Plot

Within the very first minute, it’s immediately clear that we’re dealing with a 1970s Bigfoot vehicle, as the pleasant melody of some country song starts playing right away. After all, what Bigfoot film could possibly do without that? In fact, in some of the previously mentioned titles, the main song was the best thing about the entire movie.

As the title and the names of the credited actors flicker across the screen, we see a snowy wonderland in the background—albeit in abysmal image quality. A dog sled transports a mysterious crate through the snow. Eventually, the two hunters stop, light a campfire, and a forceful kick against the crate, accompanied by the words “shut up you little beast,” already tells the attentive viewer that something is inside—perhaps even the titular Bigfoot.

He appears shortly thereafter, or rather his arm does, dragging the unfortunate soul sitting by the campfire out of frame. The other hunter soon becomes a victim of the white, shaggy beast as well, though he manages, with his last remaining strength, to flee onto the dog sled, which carries him back to “civilization.”

Naturally, this draws the attention of the local sheriff, and a very leisurely manhunt for the mysterious creature begins.

Review

And yes, to make matters worse, this is also a film by Bill Rebane, sometimes referred to as the “Ed Wood of the Midwest.” His body of work includes titles such as The Giant Spider Invasion (1977), Twister’s Revenge (1988), and The Alpha Incident (1978), as well as the utterly dreadful Monster A Go-Go (1965), which he didn’t actually finish himself—Herschell Gordon Lewis did.

Arrow even dedicated an entire box set titled Weird Wisconsin to him, complete with a documentary.

None of Rebane’s films could reasonably be called “good,” but anyone expecting quality from a Bill Rebane movie is already delusional. The question here is whether Rebane can at least manage to provide some entertainment for once, instead of boring the viewer to death with endless talking.

Well… sort of.

The screenplay was written by Rebane himself and Ingrid Neumayer, who had already written The Alpha Incident, which doesn’t exactly inspire confidence—especially since she has little else to her name. After a decent opening that already shows Bigfoot in full (albeit briefly), the film continues in typical Rebane fashion: people talk, and then they talk some more.

The sheriff visits the injured man in the hospital. His colleague Garrett sits at home and later wanders around with a mountain man named Jake. There’s no real plot or conflict to speak of—aside from Bigfoot roaming the forest and killing people.

Of course, the greedy capitalist archetype can’t be missing either. Businessman Olsen wants to turn the poor creature into cash. When he puts a bounty on Bigfoot, more hunters join the chase, though a real conflict between him and the good-natured officer Garrett doesn’t emerge until near the end of the film.

Very little of importance happens in the middle section. The highlight is a slow-motion snowmobile accident. The film is never dynamic; there’s plenty of filler in the form of nature shots or simply unnecessary scenes, and the camera barely moves. There’s little in the way of spectacle aside from the Bigfoots themselves—only the large one kills, while the smaller one peacefully strolls through the woods.

The whole thing is unimaginative, devoid of any special ideas, generic, and completely lacking even a hint of liberating irony. It looks exactly like all those other films featuring roaming humanoid monsters. Trimming a few minutes might have helped, but honestly, the whole story could have been told in thirty minutes.

The locations are limited to a few boring houses and the forest. Still, anyone who could find something appealing in other Bigfoot films might also draw something positive from the scenery here, which does look quite nice—even in poor image quality. Personally, I enjoy these isolated American forests as film settings.

Thanks to a surprisingly effective and subtle soundtrack—at times genuinely reminiscent of Carpenter’s The Thing—the film occasionally even manages to create atmosphere, something I never thought I’d experience in a Rebane film. This doesn’t mean he suddenly “improved,” of course; the atmosphere mostly stems from the presence of snow and trees, and even then only to a limited degree.

The acting is limited and wooden. Stafford Morgan leaves no impression whatsoever as Officer Garrett. George Flower, who appeared in various cameos in John Carpenter films, plays Jake—the typical character who has already encountered the monster but has been dismissed by the townsfolk. At least he looks the part, having also appeared in The Alpha Incident, where his performance wasn’t exactly praised either.

The only standout is Richard Kennedy as businessman Olsen, if only because of his excessive overacting, which results in constant yelling and physical outbursts. His “diabolical laugh,” however, is more likely to make the audience laugh than shudder. He also appeared in Invasion of the Blood Farmers (1972), a film that would certainly deserve a review of its own.

The dialogue is, unsurprisingly, bad—but at least not so bad that it becomes unintentionally funny.

As for the Bigfoots themselves: they’re simply two people in costumes. They look unconvincing, but not laughably awful. What’s more amusing are the sounds the creatures make when they spring into action. Quality-wise, this isn’t much worse than the ape films of the 1940s—though that’s hardly a compliment for a film from 1979.

The smaller Bigfoot was played by Randolph Rebane, possibly Bill Rebane’s son—hard to say. In any case, he was involved in several of Rebane’s other productions.

The film was later distributed by Troma Entertainment, but even within Troma’s catalogue there are vastly more entertaining independent trash films. It’s therefore no surprise that Lloyd Kaufman labeled the movie one of the worst Troma releases—amusingly enough, alongside Rana. Rebane truly was a natural talent.

Anyone expecting splatter because of the Troma label will be disappointed yet again. The only red seen here comes from minor abrasions.

Conclusion

Anyone who isn’t a Bigfoot fan will either be unaware of this film or wisely steer clear of it—which isn’t hard, given that it only appeared in a US box set and exists in Germany solely as a rare VHS. (I’m still waiting for the glossy mediabook, dear labels!)

It’s definitely not Rebane’s worst film—nothing tops The Giant Spider Invasion or Monster A Go-Go—but it’s simply not entertaining. The few Bigfoot attacks are decent enough, but they can’t sustain interest across ninety minutes of talking and aimless wandering.

Still, I can’t quite bring myself to hate the film. It isn’t a total failure, after all. And yet, I’m still waiting for a truly entertaining Bigfoot film from the 1970s. Will I ever find one?

For now, the Sasquatch continues his existence in Asylum productions like Bigfoot (2012) or found-footage efforts such as The Bigfoot Tapes (2012). Let’s see if something genuinely good ever comes along…