Murders in the Rue Morgue – Review

Introduction

After a string of rather unentertaining viewings lately, I felt the urge to watch something “good” again (if that word even applies on a site like this) and browsed through my film collection, once more getting stuck on the Classic Chiller Collection, which I genuinely appreciate. More specifically, I landed on the edition dedicated to Universal’s 1932 horror film Murders in the Rue Morgue.

In the end, I felt this made for a suitable candidate for another review, as it also gave me the opportunity to revisit one of my favorite topics. I already covered the 1950s in my review of The Man from Planet X (also part of the Chiller series), cheap monster movies with titles like The Being and the various Bigfoot films, and Troma splatter with Rabid Grannies.

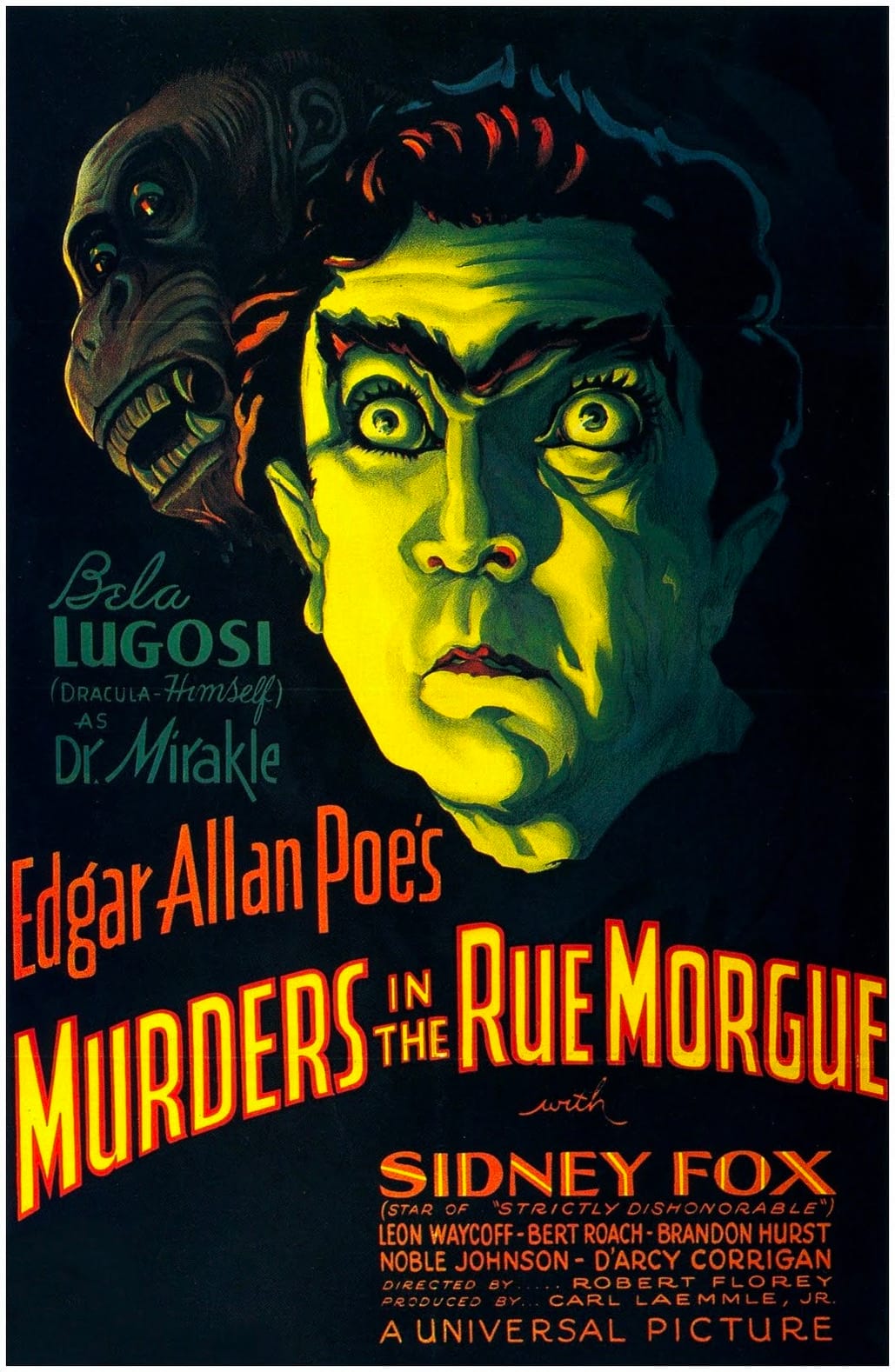

So it was about time to go back to the beginnings. And while Murders in the Rue Morgue is certainly not the most famous—or most popular or influential—entry in Universal’s classic horror lineup, it is still a must for me, since I consider myself a big fan of Bela Lugosi. From his iconic portrayal of the vampire count in Dracula, through the subsequent Edgar Allan Poe adaptations, his Poverty Row phase in the 1940s, and finally his (tragic) final years in the films of Ed Wood—Lugosi always delivered performances I found worth watching. If he appears in a film, that alone is reason enough for me to put it on my watchlist.

So then—into the Rue Morgue we go.

Plot

The opening immediately announces in large letters that the film is based on Edgar Allan Poe (if you believe that). After the credits fade, we see a ship on a river and an intertitle informing us that we are in Paris in the year 1845. The scene then shifts to a packed fairground, where the couple Camille and Pierre are enjoying themselves with their friend Lukas.

Oriental belly dancers are advertised, as well as an “Indian show” by someone named Cornel Haha (if I understood the name correctly), featuring “bloodthirsty savages” who “scalp their victims” (political correctness clearly wasn’t a concern here). Soon enough, however, a large banner depicting an ape comes into view, and a barker loudly advertises the attraction as “the strangest creature your eyes have ever seen.”

Naturally, the three friends enter the mysterious tent. At the entrance, they are shown to their seats by Dr. Mirakel, who soon appears on the small stage and calls the audience to order. He insists that he is “not a common carnival charlatan” and that he is not presenting “a freak or a curiosity of nature,” but a milestone of science—an ape-man, which understandably shocks the audience.

But that’s not all: Dr. Mirakel claims to be able to communicate with the ape, speaking to it in a kind of gibberish and translating, more or less, the story of Erik, who was supposedly abducted in Africa.

The camera then moves in close on Mirakel’s face as he launches into a monologue about evolution, at the end of which stands mankind. “Blasphemy!” someone cries from the audience. But Mirakel goes even further: his goal is to prove the blood relationship between ape and man by mixing their blood. He asks for a volunteer, and of course Camille, Pierre, and Lukas step forward.

Unsurprisingly, things don’t go well. The ape becomes aggressive and tears apart Camille’s hat. Dr. Mirakel is inconsolable and insists on replacing it. He only needs her name and address to send a new one. The couple refuses and leaves. Mirakel, however, has now found the perfect test subject in Camille and orders his servant Janos to follow her.

Review

And within the first fifteen minutes (of a mere sixty), it becomes immediately clear that the film is perfectly tailored to its protagonist: a mad scientist, an ape creature, strange theories, and experiments.

As usual, the whole thing is (loosely) based on a story by Edgar Allan Poe, the grand master of macabre tales, whose name has been used since the dawn of cinema by countless studios and filmmakers to give audiences the impression they were about to experience great literary classics. As with about 95% of all “Poe adaptations,” Murders in the Rue Morgue shares virtually nothing with the original story The Murders in the Rue Morgue beyond the basic premise that an ape commits murders.

Much like Universal’s later production The Raven (1935), also starring Lugosi, the film introduces a mad scientist who is ultimately responsible for the atrocities.

This is also not a classic on the level of Poe adaptations like The Black Cat (1934), nor a milestone like Frankenstein or Dracula. In fact, Lugosi’s only real high point at Universal was Dracula itself—a role the studio initially didn’t even want him for. Already the following year, Murders in the Rue Morgue presents itself as a clear B-movie. Not only was its runtime cut from 80 minutes to just under 60, but the budget was also reduced from $130,000 to $90,000. The film flopped, and Lugosi’s contract was not renewed. In other words, this is one of Universal’s less prestigious products.

But enough negativity. The film may not be a major achievement, but it still offers enough to satisfy fans. Story-wise, it follows familiar patterns that won’t surprise anyone today: Bela Lugosi plays the mad scientist, Camille is the damsel in distress, Pierre the young hero, and Lukas the comic relief—a character I personally find annoying, and one that Universal unfortunately shoehorned into several films, including Bride of Frankenstein.

Screenwriter Tom Reed was not a typical Universal writer—his work in the fantastic genre is limited to this film and parts of Bride of Frankenstein. It may also be due to the roughly twenty minutes that were cut, but the final 60-minute version ultimately feels unsatisfying. On the one hand, we get annoying filler scenes with unnecessary romantic-pathetic dialogue between Pierre and Camille (for example, him praising her looks on a balcony), as well as grating scenes featuring the comic relief Lukas.

This character could have been removed entirely without any issue. Aside from gawking stupidly and spouting a few clichés, he contributes absolutely nothing to the plot and doesn’t even appear in the finale.

Logic is also not always the film’s strong suit. Eventually, the ape-man abducts Camille, who screams her lungs out. When the residents, Pierre, and the police storm her empty room, Pierre is immediately suspected of being the murderer—despite the fact that he was present when the room was entered. This is followed by a lengthy scene in which the residents argue about what language was spoken behind the door. The “joke” culminates in a German claiming it was Italian, an Italian claiming it was Danish, and a Dane claiming it was German.

This filler material is nothing but dead weight. It advances neither the plot nor the humor, because what the audience really wants to see is the mad scientist carrying out his schemes.

In that regard, the film is somewhat disappointing. Lugosi, as always, delivers a great performance, but unfortunately he doesn’t get nearly as much screen time as one would hope within those 60 minutes. Worse still, his character is only superficially explored. We learn nothing about his past or his true motivations. Sure, he wants to prove the theory of evolution and the kinship between ape and man—a controversial topic in the 1840s—but how exactly does he intend to do that? By injecting human blood into apes? And why is the blood of his previous victims—whom he picks up off the street and later dumps into the Seine (which reminded me of Lugosi’s role in The Human Monster from 1939)—apparently unusable?

Then again, trying to find logic in the experiments of a mad scientist from a 1930s film is probably pointless. But Pierre’s actions are also only half-heartedly integrated into the story. In Poe’s original tale, a detective sets out to unravel the mystery; here, Pierre is merely a student who acquires corpses from the morgue for cash in order to study them, and somehow quickly connects the deaths to Dr. Mirakel.

That said, at 60 minutes, the story remains fairly brisk, without major lulls, and doesn’t really bore. Still, wishing for a bit more “action” is entirely justified.

The production design is likewise middling. The opening fairground scene is lively, packed with people and attractions. After that, things often feel rather sparse—especially Dr. Mirakel’s laboratory, which is very simply furnished: an ape cage, a device to restrain victims, and a few chemical containers. The morgue looks similarly bare.

The street scenes and rooftop sequences, however, are very well done and possess that unmistakable Universal atmosphere. The use of light and shadow—especially when Dr. Mirakel lurks in semi-darkness—inevitably recalls German Expressionism. This is no coincidence, as cinematographer Karl Freund, who worked on The Mummy and Metropolis, was behind the camera here as well.

Inside buildings and rooms, the camera is less dynamic due to the limited sets, but on the streets and outdoors there are some lovely camera movements. Fog is used sparingly—only in one scene, where it’s actually so thick that you can barely see anything. One downside I noticed is the near absence of music; especially during the finale, there’s practically no background score at all.

As for the effects, there isn’t much to say. This is what I’d call an “ape film,” a subgenre particularly popular in the 1940s (Lugosi himself starred in The Ape Man in 1943). It wasn’t the first of its kind, though—that honor likely goes to the lost Lon Chaney film A Blind Bargain (1922), unless I’m mistaken.

Interestingly, the film combines footage of a real ape with shots of a man in a costume. These are blended well enough to create a more or less convincing illusion, though it does feel a bit macabre when the costumed ape-man climbs walls or scurries across rooftops.

Acting-wise, Lugosi clearly dominates. I personally prefer him over Karloff, and here he delivers exactly what one would hope for: theatrical at times, occasionally whiny, launching into pathetic speeches. He’s simply perfect for such roles, and the film makes good use of his facial expressions, often moving the camera in close. His disguise—with a unibrow, curls, and a top hat—does look somewhat absurd, though.

Beyond that, we’re dealing with fairly generic characters, and accordingly unremarkable performances. Leon Ames is fine as the young hero Pierre. Sidney Fox as the damsel in distress Camille personally annoyed me, though that likely has more to do with the role than her acting. Beyond screaming, fainting, and looking pretty, she isn’t required to do much. As for Bert Roach as Lukas, I’ve already said everything there is to say—his character is completely superfluous and adds nothing whatsoever.

I own the film as The Murders in the Rue Morgue in Ostalgica’s Classic Chiller Collection, presented in a slipcase. The Blu-ray image quality is quite good. As usual, Ostalgica also provides a new German dub (by Bodo Traber), but I only listened to the first fifteen minutes—especially with Lugosi films, I prefer the original version with subtitles. As a bonus, the set even includes The Death Kiss, also starring the Hungarian actor, as well as an audio commentary.

Conclusion

All of this probably sounds more negative than the film ultimately feels when watching it. Sure, Murders in the Rue Morgue is far from a Universal highlight, and much more could have been done with the material. Still, at just 60 minutes, it offers breezy B-movie entertainment for fans of old-fashioned horror—above all thanks to Bela Lugosi.