Introduction:

When it comes to associating film monsters with Hammer Films, two names immediately come to mind: Dracula and Frankenstein. These were the characters that opened the doors to international fame for the small British production company. It all began in 1957 with The Curse of Frankenstein, followed the very next year by Dracula. The former, in particular, made it possible for Hammer to reimagine further classic Universal monsters.

After the enormous success of The Curse of Frankenstein—which reportedly earned nearly seventy times its modest budget of $500,000—the struggling Universal Studios were taken by surprise. This eventually led to an official collaboration, allowing Hammer to stop worrying about copyright issues. While Mary Shelley’s novel was already in the public domain, the original screenplay had nevertheless been revised.

This success naturally led to further entries in the Frankenstein series, all starring Peter Cushing as the now-iconic Baron Frankenstein. Christopher Lee, who would soon make Dracula his trademark role, played the monster only in the original film.

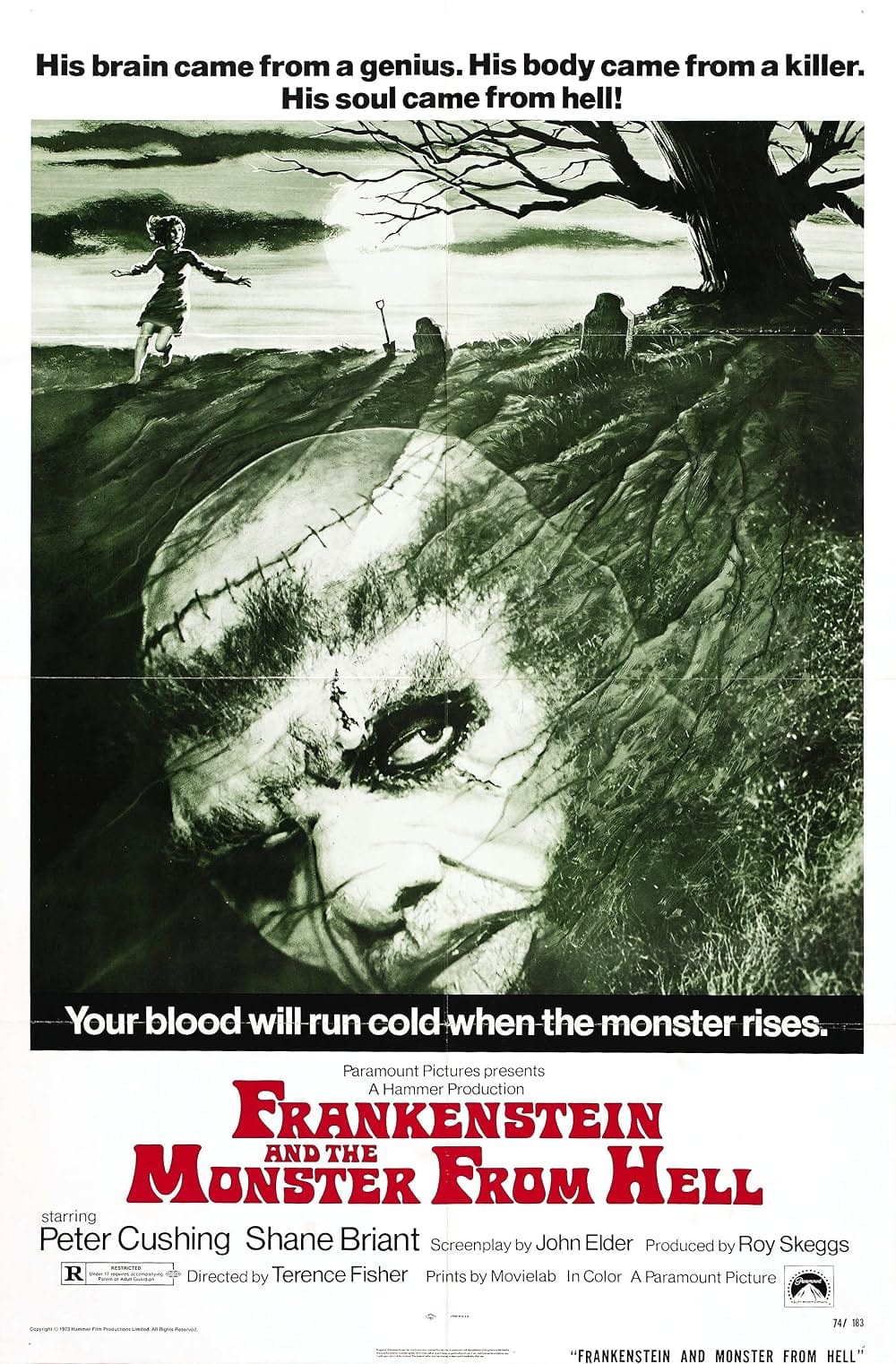

Over the next seventeen years, four additional Frankenstein films followed, three of them directed by Terence Fisher, Hammer’s defining filmmaker and also the director of the original. These were The Evil of Frankenstein (1964), Frankenstein Created Woman (1967), Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969), and finally Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell. The latter was completed in 1972 but not released until two years later, in 1974—and it is the subject of this review.

One might reasonably assume that a Hammer Frankenstein film wouldn’t belong on a site dedicated to “bad movies.” Hammer productions were B-films and, despite their early successes, never major prestige pictures—but to label them outright as “bad” would be questionable at best.

By 1972, however, the studio was already in decline. The traditional Gothic horror of the late 1950s and 1960s no longer promised financial success, and Hammer had failed to adapt to the more explicit, brutal horror that audiences increasingly demanded. Graphic violence had never been Hammer’s style, not least due to British censorship laws. As profits dwindled, Hammer’s fortunes faded.

Still, for one final Frankenstein entry, studio head Michael Carreras assembled the old guard once more. This included not only Peter Cushing and Terence Fisher—returning to the director’s chair after nearly three years—but also screenwriter Anthony Hinds. Although Hinds had already stepped down from his executive role years earlier, he contributed the script under a pseudonym.

Ultimately, Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell was produced on a modest budget of around £140,000 and shot at Elstree Studios. Hammer had already been forced to abandon their beloved Bray Studios in 1970.

But enough about Hammer’s slow demise. What, then, does the final Frankenstein film actually offer?

Plot:

A Hammer production can often be identified not only by its distinctive blood-red, swirling title font proclaiming “A Hammer Production,” but also by its familiar opening: a quiet, ominous piece of music accompanying a nighttime scene in a graveyard. Sure enough, a grave robber is at work, exhuming a corpse. After narrowly avoiding detection by a passing police officer, he transports the body straight to his employer.

That employer is Simon Helder, a young medical student who not only admires Frankenstein and studies his writings, but has already begun following in his footsteps. He is in the process of assembling enough body parts to create a new human being. The grave robber clearly disapproves of this endeavor, but the money is enough to keep him cooperative.

Later that evening, the robber is recognized in a tavern by the very policeman who saw him in the cemetery and is promptly arrested—after revealing the identity of his client. The officer pays Simon a visit and discovers his collection of stolen body parts. A brief scuffle ensues, during which a jar filled with eyeballs is smashed on the floor. That’s enough for the law: Simon is arrested for witchcraft and brought before the same court that once condemned Frankenstein himself.

The judge shows mercy, sentencing Simon to five years in a mental institution. Upon arrival, he is subjected to a humiliating initiation ritual—being hosed down with a fire hose in front of the other inmates—and introduced to the alcoholic asylum director. He also meets the institution’s physician, whom he recognizes as the supposedly deceased Baron Frankenstein himself. Frankenstein promptly appoints Simon as his assistant.

Review:

At first glance, Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell appears to follow directly in the footsteps of its predecessors. The seemingly indomitable Baron Frankenstein simply cannot abandon his experiments, continuing his work despite countless failures. After a brief introduction to Simon Helder and his conviction—which the film dispatches with quickly—the story moves to its primary setting, which it never leaves for the remaining eighty minutes: the mental asylum.

It is here that the film’s reduced budget becomes immediately apparent. Whereas earlier entries—and the Dracula films as well—lavishly celebrated their Gothic settings, this location feels significantly less elegant and far less epic. The sets are smaller, and exterior shots are rare. Those that do appear are clearly recognizable as unconvincing miniature models, something decidedly untypical for Hammer.

Despite these limitations, the film still manages to conjure a distinctly Hammer-like atmosphere, largely thanks to its asylum setting. The narrow, dungeon-like corridors evoke a sense of gloom, while torchlight and Victorian costumes maintain the familiar Hammer Gothic aesthetic—even if the trademark fog is conspicuously absent.

Hammer films, however, were never truly defined by grand set pieces or massive spectacle. What consistently set them apart was their cast. And here, Peter Cushing once again towers above everyone else. His entrance after roughly fifteen minutes—dressed impeccably in a tailcoat and tall black top hat—instantly elevates the film.

This time, he sports a somewhat artificial-looking blond wig (which he reportedly felt made him resemble Helen Hayes) and appears visibly aged and gaunt following the traumatic death of his wife the previous year. Yet his portrayal of the Baron remains as compelling as ever. He embodies a man of charm and elegance, masking an inner ruthlessness—a madman torn between scientific brilliance and an obsessive pursuit of perfection, regardless of the cost.

The rest of the cast is perfectly serviceable. The young and idealistic Simon is played by Shane Briant, who had previously appeared in Hammer’s Captain Kronos: Vampire Hunter (1973) and Demons of the Mind (1972), and he acquits himself well here. Beyond that, the Frankenstein creature itself is, unsurprisingly, of central importance.

As noted earlier, the monster is no longer played by Christopher Lee, who by this point had largely distanced himself from Hammer altogether. Due to the limited budget, the creature differs significantly from previous incarnations. Instead of an expressive makeup design, the film opts for a full-body mask—a more cost-effective costume approach. This renders the monster less human and more animalistic, resembling something closer to Bigfoot or a Yeti than a man.

The role is performed by David Prowse, who had already donned the costume in The Horror of Frankenstein (1970). This incarnation of the creature is no longer a helpless victim, as in the 1957 original, but an immensely strong being—still marked by sadness and serving as a reflection of its creator’s moral decay.

This film also distinguishes itself from earlier Hammer entries in other ways. It is clear that the studio was attempting—perhaps desperately—to adapt to the changing times. The violence is more explicit, and Frankenstein’s atrocities are shown more openly. Brain operations are depicted in detail, and while the effects may look like obvious props today, it remains striking to see Peter Cushing performing in scenes of this relative brutality.

The result is an unusual blend of bloodier Euro-horror elements and classic Hammer atmosphere. While the combination may feel strange at first, the film never goes too far and ultimately strikes a reasonable balance—even if moments like Frankenstein biting through a blood tube or accidentally crushing a brain into mush border on the grotesque.

The asylum inmates, briefly introduced during an early inspection, also contribute to the film’s bleak tone. Though they primarily exist as “material” for Frankenstein’s experiments, they mirror his fractured psyche: a man who believes himself to be God, another suffering from brain damage yet capable of creating beautiful sculptures. Rarely has a Hammer film felt so desolate in its character portrayals.

Here, Baron Frankenstein has fully devolved into madness. Any remaining idealism exists only on the surface; beneath it lies a man conducting experiments solely for his own sake, devoid of direction or moral restraint.

Conclusion:

As the final entry in the franchise, Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell stands out as a genuinely distinctive film. Despite limited resources and a confined setting, Terence Fisher—directing his final film—manages to sustain interest throughout. The pacing is tight, with no noticeable lulls, and the film never becomes boring.

Peter Cushing remains a pleasure to watch, even if it is evident that his best years were behind him. His performance here, however, suffers none for it. Hammer had hoped that this new, more violent direction might revive the studio’s fortunes, and the open-ended conclusion certainly leaves room for further installments.

As history shows, that revival never came. The film performed poorly, particularly in the United States, where it reportedly earned a mere £3,000 in its opening week. Hammer’s fate was effectively sealed. The film never received a theatrical release in Germany and was only later given a competent German dub as part of a release by Anolis. A few more obscure attempts followed, such as The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (1974), but when even that experiment—combining traditional horror with martial arts—failed, Hammer filed for bankruptcy in 1979 after their final theatrical release.

That said, for Hammer enthusiasts who already appreciate the studio’s more traditional offerings, this final Frankenstein entry is certainly worth watching. It delivers the expected atmosphere, a consistently excellent Peter Cushing, and a willingness to explore more graphic territory. It may not have worked at the time—but today, it works all the better for me.